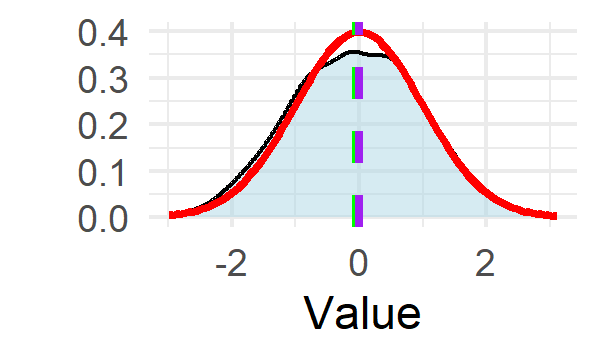

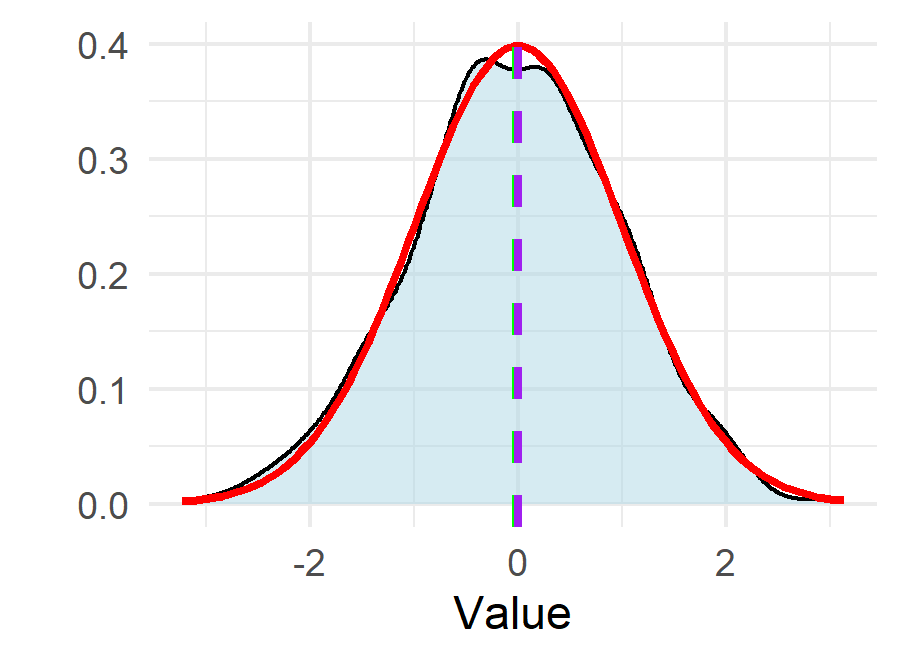

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Descriptive Statistics ] .author[ ### Pablo E. Gutiérrez-Fonseca ] .date[ ### 2025-01-15 (updated: 2025-02-05) ] --- <style>.xe__progress-bar__container { bottom:0; opacity: 1; position:absolute; right:0; left: 0; } .xe__progress-bar { height: 4px; background-color: #0051BA; width: calc(var(--slide-current) / var(--slide-total) * 100%); } .remark-visible .xe__progress-bar { animation: xe__progress-bar__wipe 200ms forwards; animation-timing-function: cubic-bezier(.86,0,.07,1); } @keyframes xe__progress-bar__wipe { 0% { width: calc(var(--slide-previous) / var(--slide-total) * 100%); } 100% { width: calc(var(--slide-current) / var(--slide-total) * 100%); } }</style> # Why describe data? - Determine if our sample reflects the population of interest. - Identify outliers. - Obtain metrics necessary for inferential tests. - Understand the distribution of our data values (i.e., test for normality). - Identify the type of statistical test to run. --- # Data description and visualization - We can examine our data and run statistical tests to see if the distribution approximates a normal curve. - Typically, we start by visualizing our data. .center[ <!-- --> ] --- # Histogram basic - Continuous data are most commonly visualized using Histograms. - Histograms display the distribution of data by grouping values into intervals or bins, allowing for an understanding of the frequency and spread of the data. <img src="fig/Histogram.jpg" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Box and Whisker Basics - Box plots are used to visualize the distribution of continuous data, showing the **median**, **interquartile range (IQR)**, and **potential outliers**. - The **box** represents the middle 50% of the data (from the first quartile \( Q1 \) to the third quartile \( Q3 \)). - The **line inside the box** shows the median (50th percentile). - **Whiskers** extend from the box to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 times the IQR from \( Q1 \) and \( Q3 \). - **Data points outside the whiskers** are considered potential **outliers**. <img src="fig/box.jpg" width="40%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. - Data and their associated distributions can be described in four primary way: - Central Tendency (mean, median, mode) - Variability (standard deviation, variance, quantiles, range) - Skew - Kurtosis (Peakedness) --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. - Data and their associated distributions can be described in four primary way: - **Central Tendency (mean, median, mode)** - Variability (standard deviation, variance, quantiles) - Skew - Kurtosis (Peakedness) --- # Central tendency - **Mean `\(\frac{\sum X}{n}\)` **: - Most often used measure of central tendency. - Works well with normal and relatively normal curves. -- - **Median (50th Percentile)**: - No formula. Rank order observations then find the middle. - The second most used measure of central tendency. - Works best with highly skewed populations. -- - **Mode (Most Frequent Score)**: - Least used measure of central tendency. - Works best for highly irregular and multimodal distributions. --- # Central tendency: Mean $$ \bar{X} = \frac{\sum X}{n} $$ - where: - ** `\({X}\)` ** represents individual data points and ** `\(n\)` ** is the number of observations. -- - Sample mean is the measure of central tendency that best represents the population mean. -- - Mean is **very** sensitive to extreme scores that can "skew" or distort findings. --- # Central tendency: Median - Percentiles are used to define the percent of cases equal to and below a certain point on a distribution. - The median **is the 50th percentile**, meaning *half of all observations fall at or below this value*. - But lots of other percentiles are also important. --- # A little about Percentiles .pull-left[ - Quartiles (i.e., divide data into four equal parts: 25%, 50%, 75%) are a common percentile used to represent the value below which. - 25% (Q1 or first quartile) - 75% (Q3 or third quartile) ] .pull-right[ <img src="fig/quartiles.jpg" width="100%" /> ] --- # When to use What .pull-left[ - Use the **Mode** when the data are categorical: - **Mode**: is the value that occurs most frequently in your data. - This is because having the same value occur for measurements with many significant digits is highly unlikely. - Use the **Median** when you have extreme scores: - **Median**: is simply the value that falls in the middle of all your data. - Use the **Mean** the rest of the time. ] .pull-right[ .middle[ .center[ <img src="fig/CnetralTendency.jpg" width="60%" /> ]]] --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. - Data and their associated distributions can be described in four primary way: - Central Tendency (mean, median, mode) - **Variability (standard deviation, variance, quantiles)** - Skew - Kurtosis (Peakedness) --- # Variability .center[ <img src="fig/variability.png" width="80%" /> ] --- # Variability: Standard Deviation - **Standard Deviation** measures how spread out the numbers in a dataset are around the mean. -- - The sample standard deviation `\(s\)` is calculated as: `$$s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n - 1}}$$` - `\(s\)` : The **sample standard deviation**, which measures the spread or variability of the data points around the sample mean `\(\bar{x}\)`. - `\(n\)`: The **sample size**, or the number of observations in the dataset. - `\(x_i\)`: Each individual data point in the sample. - `\(\bar{x}\)`: The **sample mean**, or the average of the sample data. --- # Variability: Variance - **Variance** measures the average of the squared differences from the mean, indicating how spread out the data points are. - The variance `\(\sigma^2\)` is calculated as: `$$s^2 = \frac{\sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n - 1}$$` - **Variance is always larger than the Standard Deviation (SD)** because variance is the square of SD. - For example, if the SD is 3, the variance will be `\(3^2 = 9\)`. --- # Variability: Range - **Range** is the difference between the largest and smallest values in a dataset, providing a measure of the spread or dispersion of the data. -- - The range is calculated as: `$$\text{Range} = \text{max}(x) - \text{min}(x)$$` --- # Percentiles are useful for spread too - You can use percentiles to get a feel for how spread out the data is and where most of your observations are contained: - Inter-quartile range (IQR) = Q3 - Q1 .center[ <img src="fig/iqr.png" width="45%" /> ] --- # Identifying outliers - An **outlier** is an observation that lies outside the overall pattern of a distribution (Moore and McCabe 1999). -- - Usually, the presence of an outlier indicates some sort of problem. (e.g. an error in measurement or sample selection). -- - But they may also be an indicator of novel data or identification of unique and exciting observations. --- # Identifying outliers - The first and third quantiles (Q1 and Q3) are often calculated to identify outliers. -- - One method for systematically identifying outliers uses: - Q1 - (1.5 * the inter-quartile range) - Q3 + (1.5 * the inter-quartile range) --- # When to use What - Use the **Standard deviation (SD)** in most cases. - SD quantifies how far, on average, each observation is from the mean. - The larger the SD, the more highly variable your data. -- - Use **range (R)** when describing predictive models. - R is simply the maximum minus the minimum value in your data set. - R is important when modeling or making predictions, since your algorithms are valid only over the range of values used to calibrate your predictive model. -- - Use the **IQR** to identify and test potential outliers in your data. --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. - Data and their associated distributions can be described in four primary way: - Central Tendency (mean, median, mode) - Variability (standard deviation, variance, quantiles) - **Skew** - Kurtosis (Peakedness) --- # Skewness - **Skewness**: This metric quantifies how balanced (symmetrical) your distribution curve is. .center[ <img src="fig/skewness.png" width="80%" /> ] --- # Skewness - A **normal distribution** will have its mean and median values located somewhere near the center of its range. .center[ <img src="fig/skewness.png" width="80%" /> ] --- # Skewness - Skew of this peak away from center is common when extreme values pull the median away from the mean. .center[ <img src="fig/skewness.png" width="80%" /> ] --- # Skewness - **Positive Skew**: the "slide" takes you in a positive direction. - The mean is bigger than the median (which is why the slide is being pulled to higher values). - **Negative Skew**: the "slide" takes you in a negative direction. - The mean is smaller than the median (which is why the slide is being pulled to lower values). .center[ <img src="fig/skewness.png" width="60%" /> ] --- # Calculating Skew - Negative value = Negative Skew. - Positive value = Positive Skew. - Zero = Normal distribution. `$$\text{Skewness} = \frac{3(\bar{X} - \text{Median})}{\text{SD}}$$` - where: - `\(\bar{X}\)` is the **sample mean**, representing the average of all data points. - **Median** is the middle value in a dataset when sorted in ascending or descending order. - **SD** (Standard Deviation) measures the spread of the data points around the mean. --- # Skewness: Significant? - To determine if this deviation from zero in the skew statistic is likely a significant departure from normality, compare it to the **standard error of skew (ses)**. - If the skew you have calculated is more than **2 times the ses**, then you likely have significant skew, which means you have **non normal data** and should consider a nonparametric test for your statistical analyses $$ \begin{array}{cc} ses = \sqrt{\frac{6}{n}} & \hspace{1cm} \text{Skewness} = \frac{3(\bar{X} - \text{Median})}{\text{SD}} \end{array} $$ --- # Metrics to Describe data distribution. - Data and their associated distributions can be described in four primary way: - Central Tendency (mean, median, mode) - Variability (standard deviation, variance, quantiles) - Skew - **Kurtosis (Peakedness)** --- # Kurtosis - **Kurtosis** is simply a measure of how pointy or flat the peak of your distribution curve is. - Any deviation from a bell shape, with the peak either too flat (platykurtic) or too peaked (leptokurtic), suggests that your data are not normally distributed. .center[ <img src="fig/kurtosis.png" width="50%" /> ] --- # Kurtosis - Positive values = Leptokurtic. - Zero = Mesokurtic = normal (bell-shaped). - Negative values = Platykurtic. $$ \text{Kurtosis} = \frac{\sum(\left( \frac{x_i - \bar{X}}{\text{SD}} \right)^4 - 3)}{n} $$ - where: - `\(x_i\)` represents each individual data point. - `\(\bar{X}\)` is the **sample mean**, the average of all data points. - **SD** (Standard Deviation) is the measure of how spread out the data points are from the mean. - `\(n\)` is the number of data points in the sample. - The subtraction of 3 is to adjust for the kurtosis of a normal distribution, which has a kurtosis of 3. --- # Kurtosis: Significant? - To determine if this deviation from zero in the kurtosis statistic is likely a significant departure from normality, compare it to the **standard error of kurtosis (sek)**. - If the kurtosis you have calculated is more than **twice the sek**, you likely have **non normal data** and should consider a nonparametric test for your statistical analyses. $$ \begin{array}{cc} sek = \sqrt{\frac{24}{n}} & \hspace{2cm} \text{Kurtosis} = \frac{\sum \left( \frac{x_i - \bar{X}}{\text{SD}} \right)^4 - 3}{n} \end{array} $$ --- # Some Visual Examples - How can climate change? - Change in **central tendency**. .center[ <img src="fig/climate1.png" width="60%" /> ] --- # Some Visual Examples - How can climate change? - Change in **spread and shape**. .center[ <img src="fig/climate2.png" width="60%" /> ] --- # Some Visual Examples - How can climate change? - Change in **both**. .center[ <img src="fig/climate3.png" width="60%" /> ] --- # Data Distributions --- # Data Distributions - There are various types of data distributions, each with its own unique properties and implications. - **In nature, most data are normally distributed**. - The central limit theorem (CLT) states that the distribution of sample means approximates a normal distribution as the sample size gets larger, regardless of the population's distribution. $$ \bar{X}_n \sim N\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\right) $$ - The sample mean `\(\bar{X}_n\)` will follow a normal distribution with mean `\(\mu\)` and standard deviation of `\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)`. - As the sample size `\(n\)` increases, the standard deviation (here: `\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\)`) decreases, improving the accuracy of the sample mean as an estimate of the population mean `\(\mu\)`. --- # Why do we care if our data is normal? - The mathematical foundations of many statistical analyses **assume that data follows a normal distribution**. If this assumption is violated, the results may still produce an answer, but the interpretation could be misleading or inaccurate. --- # Why do we care about **skew** and **kurtosis**? - Because many statistical analyses assume a normal distribution of the data, testing for normality must always be a precursor to any analysis. .pull-left[ - Normally distributed data is: 1. Unimodal (one mode) 2. Symmetrical (no SKEW) 3. Bell Shaped (no KURTOSIS) 4. Mean, Mode and Median are all centered 5. Asymptotic (tails never reach 0) ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Why do we care about **skew** and **kurtosis**? - We can examine all of these different descriptors individually, but the easiest and most complete way to test for normality is to test the **goodness of fit** for a normal distribution. .pull-left[ ``` r # Generate data from a normal distribution set.seed(123) data <- rnorm(100,mean=0,sd=1) # Shapiro-Wilk normality test shapiro.test(data) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: data *## W = 0.99388, p-value = 0.9349 ``` ] .pull-right[ ] --- # Why do we care about **skew** and **kurtosis**? - We can examine all of these different descriptors individually, but the easiest and most complete way to test for normality is to test the **goodness of fit** for a normal distribution. .pull-left[ ``` r # Generate data from a normal distribution set.seed(123) data <- rnorm(100,mean=0,sd=1) # Shapiro-Wilk normality test shapiro.test(data) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: data *## W = 0.99388, p-value = 0.9349 ``` ] .pull-right[ - Interpretate `shapiro.tets()`: - Null hypothesis `\(H_0\)`: The data is normally distributed. - Alternative hypothesis `\(H_1\)`: The data is not normally distributed. ] --- # Why do we care about **skew** and **kurtosis**? - We can examine all of these different descriptors individually, but the easiest and most complete way to test for normality is to test the **goodness of fit** for a normal distribution. .pull-left[ ``` r # Generate data from a normal distribution set.seed(123) data <- rnorm(100,mean=0,sd=1) # Shapiro-Wilk normality test shapiro.test(data) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: data *## W = 0.99388, p-value = 0.9349 ``` ] .pull-right[ - Interpretate `shapiro.tets()`: - Null hypothesis `\(H_0\)`: The data is normally distributed. - Alternative hypothesis `\(H_1\)`: The data is not normally distributed. - **Larger p-value (p > 0.05)**: Fail to reject the null hypothesis; the data is likely **normally distributed**. - **Smaller p-value (p < 0.05)**: Reject the null hypothesis; the data **is not normally distributed**. ] --- # What to do about non-normal data? - Once you discover that your data is non-normal you have several options: - Analyze and potentially remove outliers - Transform the data mathematically - Conduct non-parametric analyses --- # Outliers? - How to find outliers: - Outlier box plots (visual) use the IQR * 1.5 threshold. - **IQR**: `\(Q_3 - Q_1\)` - **Lower Threshold**: `\(Q_1 - (1.5 * \text{IQR})\)` - **Upper Threshold**: `\(Q_3 + (1.5 * \text{IQR})\)` - These can help identify potential outliers but **do not justify their removal**. - Sometimes outliers are **real, correct (although extreme) observations** that we are truly interested in. - We can only remove outliers if we know the data is **incorrect** --- # Working with non-normal Data. - Transformations: - To transform your data, apply a mathematical function to each observation, then use these numbers in your statistical test. - There are an infinite number of transformations you could use, but it is better to use one common to our field. --- # Working with non-normal Data. - Non-normal data happens. Especially with counts, percents, rare events. .pull-left[ - Common transformations in our field: - square-root: for moderate skew. - log: for positively skewed data. - Inverse: for severe skew. ] .pull-right[ <img src="fig/transformation.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- # Square root Transformation - **Square-root transformation**: This consists of taking the square root of each observation. - In R use: `sqrt(X)`. ``` r data <- c(1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100) # Apply square-root transformation sqrt_data <- sqrt(data) # Goodness of fit test shapiro.test(sqrt_data) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: sqrt_data *## W = 0.97016, p-value = 0.8924 ``` --- # Square root Transformation - If you apply a square root to a continuous variable that contains **values negative values, decimals and values above 1**, you are treating some numbers differently than others. - So a constant must be added to move the minimum value of the distribution to 1. --- # Log Transformation - Many variables in biology have log-normal distributions. - In R use: `log(X)` or `log10(X)`. ``` r # Sample data (e.g., positive values) data <- c(1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000) # Apply log transformation (log base 10) log_data <- log10(data) # Goodness of fit test shapiro.test(log_data) ``` ``` ## ## Shapiro-Wilk normality test ## ## data: log_data *## W = 0.98189, p-value = 0.9606 ``` --- # Log Transformation - The logarithm of any **negative number is undefined and log functions treat decimals differently than numbers >1**. - So a constant must be added to move the minimum value of the distribution to 1. --- # Inverse transformation - **Inverse transformation**: This consists of taking the inverse \( X^{-1} \) of a number. - In R use: `1/x` or `x^-1` ``` r # Sample data (e.g., positive values) data <- c(1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64) # Apply inverse transformation (reciprocal) inverse_data <- 1 / data ``` - Tends to make big numbers small and small numbers big a constant must be added to move the minimum value of the distribution to 1 --- # Reflecting Transformations - Each of these transformations can be adjusted for negative skew by taking the reflection. - To reflect a value, **multiply data by -1**, and then add a constant to bring the minimum value back above 1.0. - For example: - sqrt(x) for positively skewed data, - sqrt((x*-1) + c) for negatively skewed data - log10(x) for positively skewed data, - log10(x*-1 + c) for negatively skewed data --- # Rank Transform - Rank transformation requires sorting your data and then creating a new column where each observation is assigned a rank. - For tied values, assign the average rank. - Perform all subsequent analyses on the ranked data instead of the original values. --- # Transformation Rules to Live By - Transformations work by altering the relative distances between data points. - If done correctly, all data points remain in the same relative order as prior to transformation. - However, this might be undesirable if the original variables were meant to be substantively interpretable. --- # Transformation Rules to Live By - Don't mess with your data unless you have to. - Are there true outliers? Remove and retest. - If you have to mess with it, make sure you know what you are doing. Try different transformations to see which is best. - Include these details in your methods. - Back transform to original units for reports of central tendency and variability. - Sometimes transformations don't work, don't panic, you will just get to run **nonparametric tests**.